By Morgan Stevenson-Swadling, Vassar College '24

In the early months of 1968, the then-owners of Springside asked the city of Poughkeepsie for the property to be rezoned for commercial and apartment development. This request caused a chain reaction, with concerned citizens writing to the County Executive requesting that Springside be preserved. The Dutchess County Department of Planning was made aware of Springside as a privately owned site of national and historic significance and took action to raise awareness of the site and its jeopardized state. What ensued was a 60 page report published in December of 1968, known as “Springside: A Partnership with the Environment.”

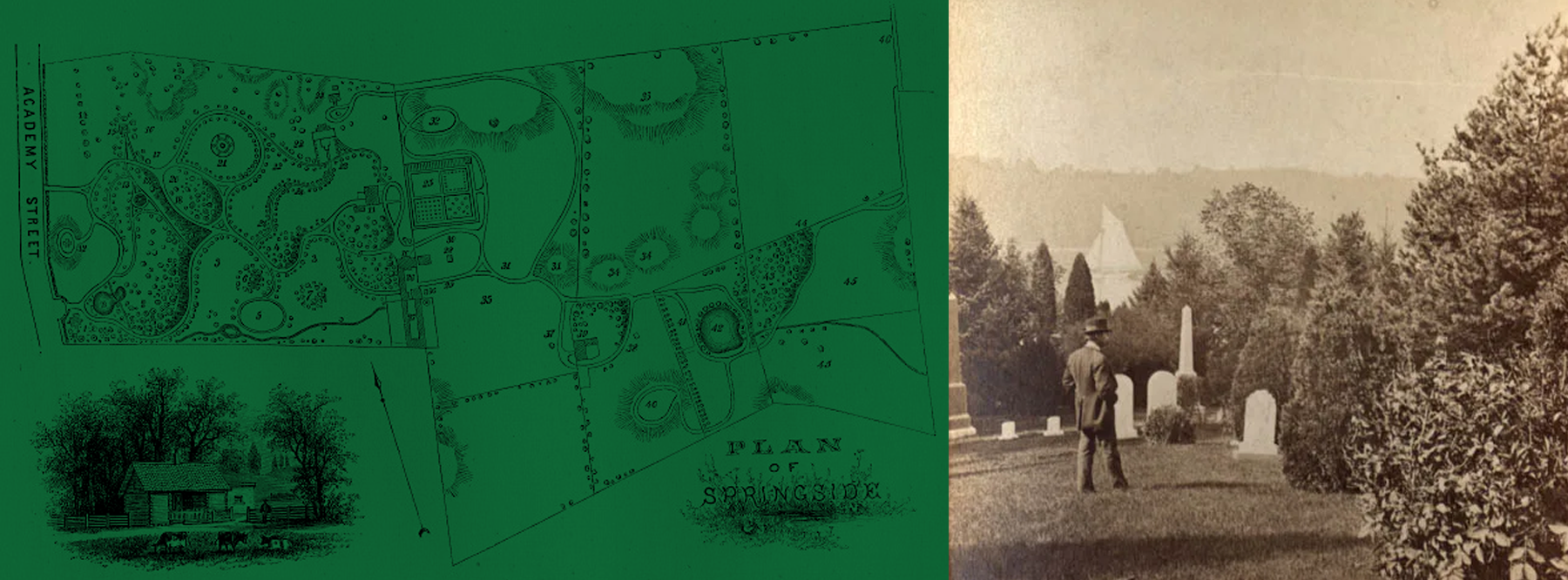

Broken up into six sections, the report began with a brief introduction before delving into the “History and Significance of Springside.” This well-detailed grounding in the site described the history of Andrew Jackson Downing’s design of the site, Vassar’s ownership, and what remained of it in the 1960s; supplemented by quotes and descriptions from respected academics in New York and beyond. Photographs of different structures on the Springside property accompanied the text, most of which were done by prolific queer photographer Rollie McKenna, a Vassar graduate. McKenna’s work was recently detailed in a retrospective curated by the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center at Vassar College.

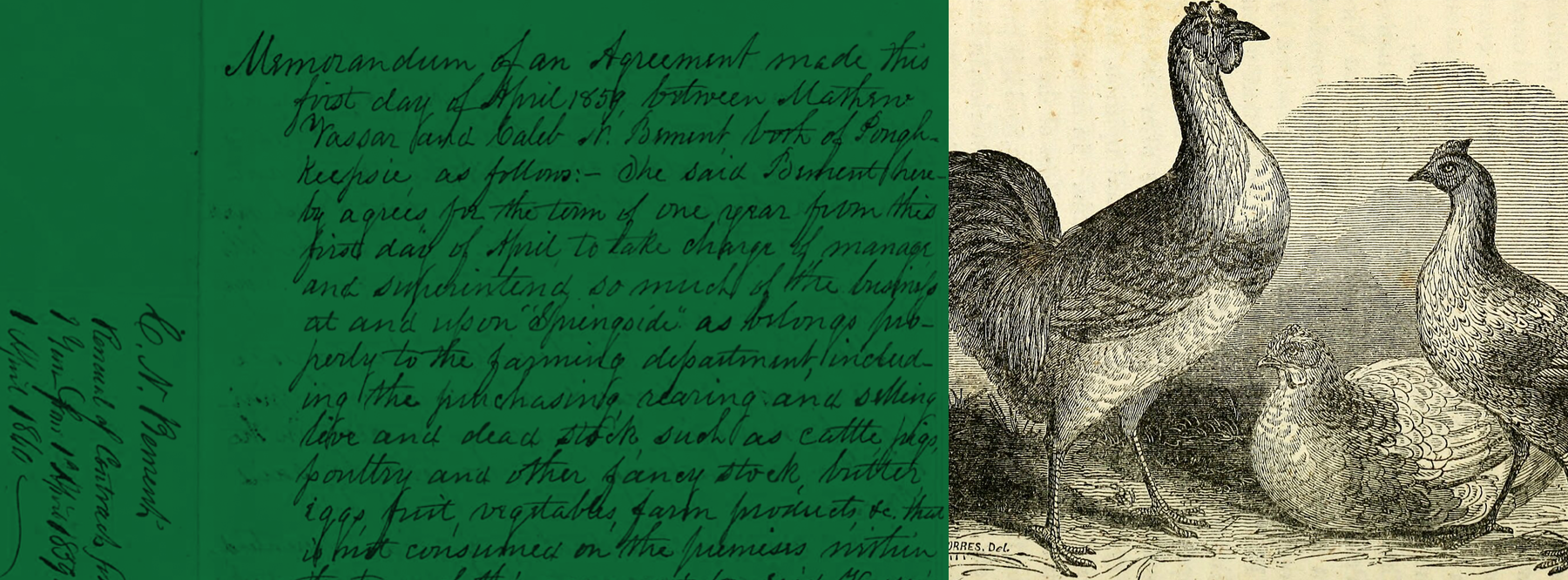

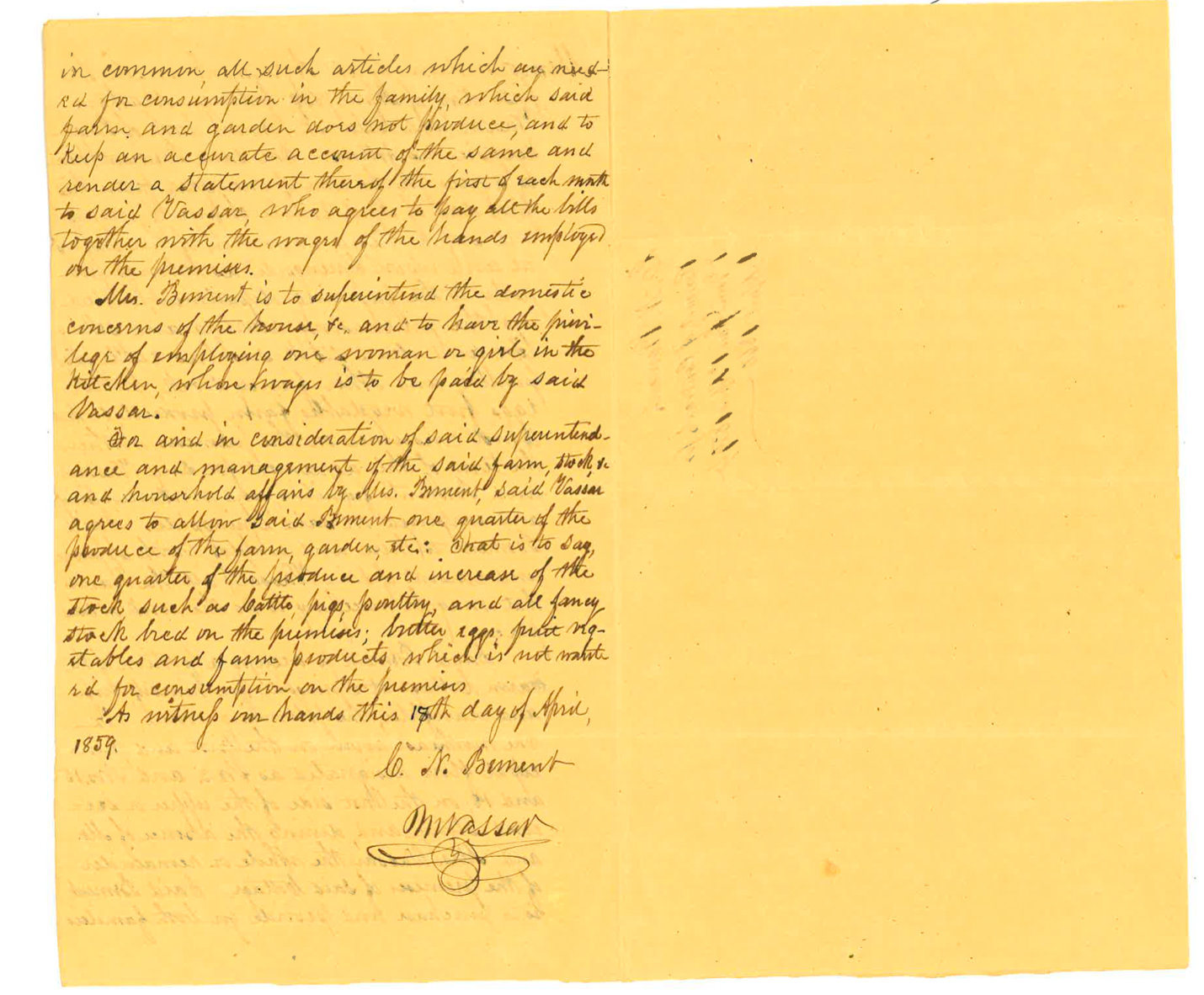

Following the historical section of the report is “Documentation,” which provides photographs, paintings, book sections, and letters on Springside. A number of books and writings dated from the nineteenth-century which cover Springside are listed. The report includes pages from Andrew Jackson Downing’s Cottage Residences, in which he directly wrote about Springside, as well as his original designs of the cottage and barn. Also included in it are paintings completed by Henry Gritten in the 1850s, which show Springside in its glorious original form.

These historic works and writings are then followed by copies of reproduced letters from the year of the 1968 report itself. Exchanges include letters written to Poughkeepsie’s mayor at the time, Richard Mitchell, from Denys P. Merys, Acting Chief of the Historical American Buildings Survey, and Murray H. Nelligan, the Assistant to Regional Director, Historic Preservation. Other letters are exchanged by three of the leading experts at the time: Thomas J. McCormick, George B. Tatum, and Jane B. Davies. The letters between these individuals show a wide breadth of knowledge, care, and interest in Springside and its significance. As written by Davies in a letter to McCormick, “Here at ‘Springside’ are found together supreme examples of nineteenth century romantic landscaping and rural architecture, the authenticated work of the most influential American exponent of both. I know of no comparable romantic estate anywhere in America. It would be a tragedy to lose this unique part of our American heritage.”

Perhaps the most moving part of the report comes in the form of “Letters of Support,” showing the outpouring of letters sent to Professor McCormick, members of Historic Boards, and several different architects. “We sincerely hope that such an impressive site within an urban community is not lost to the developers’ bulldozers” Gertrude Hankinson Briggs penned. “It still environmentally expresses…the romantic mysticism found in the literature of the 1840’s but no longer found on the ground” Professor George F. Earle muses. “Springside is a major historical monument. More than that, it points out—to a civilization increasingly alienated from its natural environment—the possibility of harmonious and meaningful relationships between man and nature. Can we afford to destroy it?” wrote Elizabeth B. Kassler.

The final section of the report concludes with articles written about the site and the necessity to preserve it. The articles are drawn from the Poughkeepsie Journal, Vassar: The Alumnae Quarterly, and Harper’s Bazaar, detailing all from the support pouring from the President of Vassar to Syracuse University students visiting and studying the site to the life of Andrew Jackson Downing. The report is then concluded by a series of Zoning Referrals.

We know now that Springside was indeed “saved,” though its story does not cease there. In March of 1969, four months after the publication of “Springside: A Partnership with the Environment,” the city council of Poughkeepsie unanimously rejected the rezoning of Springside. Later that year, Springside was declared a national landmark, only to fall victim to arson and vandalism soon thereafter. As we know well, maintenance and community organization around a site can be a challenge, and Springside is no exception. Community interest has decreased over time. One may wonder, then, why such a document as “Springside: A Partnership with the Environment” matters to the modern audience. In fact, the collection provides an example of activism so powerful that it swept over an entire community. Many of the ways in which the Poughkeepsie, Vassar, and larger New York state communities mobilized show the passion and care with which Springside has historically been regarded. Their activism should serve as a model not only for the significance of Springside, but for how we, too, should mobilize around Springside.

By Morgan Stevenson-Swadling, Vassar College '24

“The grounds are said to be well adapted for a Cemetery, and with suitable improvement may be rendered as romantic and beautiful as any public burial ground in the state.” So reported the Poughkeepsie Journal on July 6, 1850, following Matthew Vassar’s $8000 purchase of just under 50 acres of land. This site, then named Eden Hills, would later become Springside.

As detailed in Benson J. Lossing’s biography of Vassar, Vassar College and Its Founder (1867), at the start of 1850, Matthew Vassar rose to the presidency of the Poughkeepsie Board of Trustees. One of the board’s primary goals was to establish a public cemetery in the tradition of the rural cemetery movement. Vassar became chairman of the “Village Cemetery” committee and began to seek suitable grounds. The committee encountered the Eden Hills grounds, but as the result of other competitive buyers and a delay in choosing it as the official grounds, Vassar purchased it himself with the stipulation that he would sell it back to the Cemetery Association for the price he paid for it and take shares in the stock of the proposed association in the amount of $1000. The grounds were described as “undulating” with “rivulets” snaking through it and “a portion of meadow, groups of forest trees of luxuriant growth, about 10 acres laid out in an apple orchard; there are also several curious mound formations of rocky character, studded with oak, hickory, chestnut and evergreens.”

The rural cemetery movement swept across America following the creation of Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts. In the nineteenth century, there were many reasons for a shift in the state of cemeteries. Rapidly increasing urban population sizes meant that graveyards were becoming crowded public health hazards; suburban and rural areas were looked to as an alternative. Mount Auburn shifted the language of the rural cemetery from a new safety precaution and a utilitarian site to an idyllic park which inspired morality and via its beauty and construction. The combination of nature and art in the rural cemetery and the acquisitions of time would create “legacies of imperishable moral wealth” which would provide a strong improving influence on all members of society (Edward P. Humphrey, “Address on the Dedication of the Cave Hill Cemetery near Louisville, July 25, 1848”). The cemetery sought to ease the suffering of the mourner, to cause the younger to become more thoughtful and the wise more wise, to purify souls, and to increase both patriotism and religiosity.

Part of the importance of the rural cemetery was its accessibility. Mount Auburn was open to anyone who wished to purchase a lot, representing a certain level of social fluidity. As a nonprofit, the proceeds from plot sales were put solely towards maintenance and improvements of the site; which further allowed lower- or middle-class citizens such as farmers, plumbers, and small businessmen to purchase plots via goods and services that would improve Mount Auburn. As such, these “legacies of moral wealth” were designed to be accessed by all members of society.

Several other rural cemeteries followed, across New England as well as New York and Pennsylvania. The form was well-established by the time Poughkeepsie decided to develop one.

Vassar began making improvements upon the proposed cemetery site in 1850. However, with the official formation of the Cemetery Association, other grounds were decided upon and purchased on the bank of the Hudson River. Vassar decided to keep the site and transformed it into a “place of delight” for himself and his fellow citizens. Though Springside never became the cemetery it was originally intended to be, the principles upon which it was founded, and the means by which it began to be created and transformed, were based upon some of the same ideas as the Rural Cemetery. It can be understood that Springside was, and continues to be, a place of moral improvement and inspiration.

________________

Sources & Further Reading:

Finney, Patricia J. “Landscape Architecture and the “Rural” Cemetery Movement.” Center for Research Libraries. Center for Research Libraries: Summer 2012. https://www.crl.edu/focus/article/8246.

Flad, Harvey K. “Matthew Vassar’s Springside: “…the hand of Art, when guided by Taste”” in Prophet with Honor: The Career of Andrew Jackson Downing 1815-1852, Tatum, George B. and Elisabeth Blair MacDougall, eds., Washington, D.C. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1989: 219-257.

French, Stanley. “The Cemetery as Cultural Institution: The Establishment of Mount Auburn and the ‘Rural Cemetery’ Movement.” American Quarterly 26, no. 1 (1974): 37–59. https://doi.org/10.2307/2711566.

Lossing, Benson J. Vassar College and Its Founder. New York: C.A. Alvord Printer, 1867: 61-79.

Newcombe, Emma. “From Cemeteries to Suburbs: How a Romantic Movement Reshaped America.” Governing. Governing: December 22, 2022. https://www.governing.com/community/from-cemeteries-to-suburbs-how-a-romantic-movement-reshaped-america.

“Village Cemetery.” Poughkeepsie Journal. July 6, 1850. https://poughkeepsiejournal.newspapers.com/image/115238762/?terms=vassar&match=1 (accessed January 30, 2024).

Sutton, Michelle. “The Rustic Symbolism of Victorian-Era Treestones.” New York State Urban Forestry Council. New York State Urban Forestry Council: April 16, 2018. https://nysufc.org/rustic-symbolism-victorian-era-treestones/2018/04/16/.